Time.

Space.

Now.

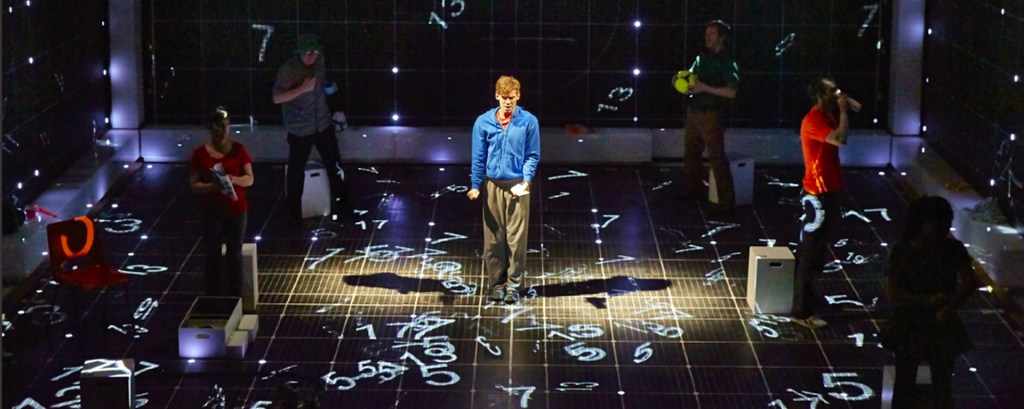

These three words accompany intersecting lines projected onto a graphic and gridded black and white stage at the beginning of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night- Time. The universality of the first two words and the immediacy of the third situate the viewer in a strange but scientifically logical place. Perhaps it is not often that we think of ourselves as points plotted on a grid (although, with Google Maps, maybe it is), but however you may think about yourself and the world, you are asked to think about it in this way—highly quantifiable and conceptually justifiable—for approximately the next two hours and thirty-five minutes of this play because this is how its main character thinks about himself and our world.

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time (a production of the National Theater, which opened in London in August of 2012 and transferred to Broadway in October 2014) is based on Mark Haddon’s 2003 novel of the same name and follows 15-year-old Christopher John Francis Boone as he attempts to pinpoint the culprit in the murder of a neighborhood dog, a crime for which Christopher was falsely accused. What takes the story beyond your standard detective procedural is that Christopher has an unspecified mental condition (likely Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism), and the situation that surrounds him and the truth of the dog’s demise are far from ordinary. Rather than being a story about man’s best friend, the play profoundly addresses the challenges of being mentally different in a complex, evolving, and relentless world whose circumstances do not always allow for precise and calculable solutions, despite what those intersecting lines on the gridded stage might suggest. The circumstance is instead a messy web of highly unquantifiable issues of family, immorality, sexuality, and mental anxiety—the discovery of which is all catalyzed by the search for truth around the dog. The show’s production has been much heralded for its “high-tech” qualities, but truthfully it employs the standard lighting, projection, and sound that grace most theatrical stages on a nightly basis. Its triumph is the implementation and integration of these devices with the story, fusing design, character, and narrative to make visible what is invisible: the mind.

Initially, the set is sparse: a gridded, cube-like structure with dimly glowing beams outlining the space’s shape. Beyond these few delineating and distinguishing lines, it is minimalist and sanitized, as if it is a room prepped for surgery. What you come to learn is that this austere atmosphere reflects the ascetic and dutifully accurate visual scape of Christopher’s mind. As the play’s director Marianne Elliot describes, “Christopher’s got a very unique and wonderful and extraordinary and imaginative brain, and the light, the set, the projections, the music, and the sound are all supporting the fact that this is inside his view of the world.”[i] The grid reinforces Christopher’s penchant for systems, precision, and routine that aligns with his way of thinking. It aligns also with his aversion to touch, a sanitized diagram that supports his physical recoil from proximity to other humans. It is this world—Christopher’s world or the way he perceives the world—that is the visual and thematic precipice of this very curious and compelling incident.

As rigid as it might initially seem, this set is also the mind of an energetic, endearing 15-year-old boy. Scenic designer Bunny Christie explained her thoughts on the space: “It needed to feel like a fun environment, more like a computer gaming room, or a club, or a nightclub, or something that had a kind of an energy or excitement to it. And I really felt like it should be a space where Christopher would feel at home.”[ii] What allows the set to truly come alive in a playful but meaningful way is that this box of lighting and projected images becomes a tool of space and perception. “Light can do a million different things,” said lighting designer Paule Constable, and in Curious Incident it is asked to be a determinant of space, thought, and emotion.[iii] Lights—not the famed theatrical spotlight or racing bulbs on a marquee, but rather flashing LEDs, beams, and screens—create an electrifying dynamism similar to that of a pinball machine or the virtual world of a video game. The simplicity of the gridded canvas of the stage allows a combination of light and projected images to create an imagined materiality consistent with Christopher’s very specific, constructed, and thoughtful world. A beam of light signifies a room in a house; a flood of projected graphics captures a busy train terminal; a moving line of LEDs chart Christopher’s path of motion; a vast projection of stars becomes the universe of Christopher’s daydreams as he imagines being an astronaut.

Beyond just designating space and location, like a map or blueprint, the lighting becomes a manifestation of Christopher’s thought process as well as his perception of his place in the world. “How [the environment is] perceived, how it’s brought to life is what the lighting designer does,” says Constable.[iv] In the early twentieth century, pioneering theatrical designer Adolphe Appia introduced this idea of light as an emotive force in the performance space. Rejecting nineteenth-century conventions of painted drops lit straight on, he favored light for its sculptural quality and employed architectonic sets (such as columns and staircases) to cast dramatic shadows, arguing: “Light is distinguished from visibility by virtue of its power to be expressive.”[v] In light of Appia’s and Constable’s congruent theories, the lighting designer becomes an agent to perception; in Curious Incident, when perception, by the character or, by extension, the audience, is integral to the telling of the story, the lighting becomes a translator. Through the use of lighting and projected images, the space of the stage becomes an illustration of Christopher’s mind, a playing field that adapts as a surrounding on a thought-by-thought basis.

Christie explains the emotional effect of this buffeting, this integration of thought and space: “At…times, as his energy levels and his anxiety tips out of control, the space can tip out of control as well so that the kind of neurons of his brain are going crazy and fizzing and the energy of that is evident on the set as well.”[vi] The character’s internal anxiety is reflected in his (and our) external space. For example, Christopher has been taught to recite exponential numbers when he feels stressed to clear his mind of a disturbing social situation. As he recites, the numbers are projected around the stage. But as his anxiety builds in panic and the coping mechanism appears to fail, the numbers overlap into a dizzying, unintelligible mess of numerals while strobe lights flash. More than just seeing a human reaction, the audience is confronted with an overwhelming spectacle as the play’s visual presence is engulfed in Christopher’s struggle. In a more subdued but no less poignant moment, the near absence of lighting also tells the story. Christopher tries to sleep in a sleeping bag. He lays alone in a dimly lit square while his parents fight, yelling boisterously in total darkness. The darkness echoes Christopher’s lack of emotional understanding of the dramatic scene, with the shiny and slippery red material of his sleeping bag reflecting the dim light in a skewed, almost pixelated manner as he rocks or writhes uncomfortably. In scenes such as these, the lighting design makes clear, aided by the otherwise unobtrusive set, that, while other characters are not insignificant, we are with Christopher on his journey; we are inside his mind. It is through his understanding of his situation and the world—his “Now” from the opening projected lines—that we, in turn, learn to empathize with his struggle.

In addition to lighting and projected images, the added element of sound further intensifies this interpretation of Christopher’s mind and emotions. Composed primarily of electronic music and mechanical sounds such as trains and beeping, the sound is both an identification of the real world as well as an extrapolation of Christopher’s view of it. The gap between the real and the imaged is the result of technical nuance: “In a realistic setting, you cannot alter the pitch or the volume … without destroying the sense of reality. Yet by subtly altering the timing of the rhythm and the length when playing the cue, you can support the emotion of the character—anxiety, impatience, reluctance, happy anticipation, or foreboding.”[vii] In the case of Curious Incident, this use of sound confronts any emotional or physical vacancy in Christopher’s scientific world, provoking his reactions to cacophonous pounding or claustrophobic hums. Digitized beeping is sometimes melodious, but often not; sometimes it is a tool for precise timekeeping and sometimes just a frustrating flurry. The lighting, projections, and sound work in harmony to heighten Christopher’s world beyond its narrative reality to the perceived realm of his mind.

Not only is the light- and sound-infused stage of Curious Incident a celebration of Christopher’s interest in science and technology, but it is also very much a representation of the brain for the modern mind. As Christie enumerated, “I was very keen that it had a sense of technology, and that it felt very contemporary and modern.”[viii] The set is so modern, perhaps, that it cleverly preys on our contemporary relationship with technology, using the entire space as a projection surface to manipulate our Digital-Age instinct to stare at any screen in our vision. It becomes a space that is simultaneously euphoric, pleasing, distracting, and frustrating, mimicking the exhilaration of our contemporary congested and over-stimulated brains, brains that constantly thirst for new information. Christopher’s world becomes an extreme reflection of our world. Societally, we have become so accustomed to being flooded with media through screens that witnessing someone’s brain treated as such feels almost plausible—until it becomes a challenge to handle, bordering on inhumane sensory assault. In the 1936 film Modern Times, Charlie Chaplin famously satirized the mechanical nature of modern man as a result of industrialization by treating the exaggerated cogs of a machine as crushing social creatures. Curious Incident similarly brings literally to mind our immersion into the modernized world, our gravitation to mechanical and digital technology, but this time a technology internalized in ways that cause the modern mind to implode. This is not to suggest Curious Incident as a cautionary tale, but rather one that accurately harnesses our modern habits in order to access the character’s extra-ordinary modern mind and its potential for obstruction.

While the audience at Curious Incident sits in the dark, separated by the traditional proscenium, its design—its scenic, lighting, and sound design, that is—bring you through the imaginary membrane of the fourth wall, bypassing the boundary of the body and plunging you into the mind of the character. As Ben Brantley, chief theater critic for the New York Times, noted in his review of the Broadway production: “It forces you to adopt, wholesale, the point of view of someone with whom you may initially feel you have little in common.”[ix] When you are seeing how Christopher John Francis Boone is thinking and feeling rather than just observing how he is behaving, Christopher becomes more relatable—not just as a human, but as a stream of thoughts and emotions that could very easily parallel our own, and might make each of us reflect on our own challenges and how they may intertwine with our brains’ functioning. As Elliott explains: “The audience feels like Christopher is them. He isn’t different from them, and he experiences things in a way that we all experience them.”[x] Ultimately the set, lighting, projections, and sound invite you into the mind of someone with a mental disability who gets frustrated just as you get frustrated, who is sad just as you are sad, and who hopes to triumph just as you hope to triumph. Beyond the dazzling lights and intrigue of the canine mystery, Curious Incident is at its core a heart-and mind-wrenching drama about a troubled child and the parents who cannot (or will not) fully care for him. It is here that the design and technical elements overcome their dazzle to become essential rather than merely spectacular. Because what is design if not a tool to aid our navigation of the world, or, when possible, help with someone else’s?

This article was originally published in Objective: The Journal of the History of Design and Curatorial Studies, Parsons School of Design, Spring/Summer 2016.

Notes

[i] Curious Broadway, “Creating Christopher’s World,” YouTube video, 2:08, May 29, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6gMH285LvbM.

[ii] Broadway.com, “Design Broadway: Tony Winner Bunny Christie on A CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME,” YouTube video, 5:13, June 17, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XQuxmYNpe4.

[iii] Meredith Lepore, “Women on Broadway: Paule Constable, The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time,” accessed December 14, 2015, http://www.levo.com/articles/careeradvice/women-in-broadwaypaule-constablethe-curious-incident-of-the-dog-in-the-night-time.

[iv] Chris Shipman, “Listen: Paule Constable on the role of a Lighting Designer,” Royal Opera House, February 20, 2013, accessed December 14, 2015, Paule Constable, http://www.roh.org.uk/news/listen-pauleconstable-on-the-role-of-a-lighting-designer.

[v] Philip Buttenvorth and Joslin McKinney, Cambridge Introduction to Scenography (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 15.

[vi] Broadway.com, “Design Broadway: Tony Winner Bunny Christie on A CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME,” YouTube video, 5:13, June 17, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XQuxmYNpe4.

[vii] Deena Kaye and James LeBrecht, Sound and Music for the Theatre: The Art and Technique of Design (Burlington, MA: Focal Press, 2013), 16.

[viii] Broadway.com, “Design Broadway: Tony Winner Bunny Christie on A CURIOUS INCIDENT OF THE DOG IN THE NIGHT-TIME,” YouTube video, 5:13, June 17, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6XQuxmYNpe4.

[ix] Ben Brantley, “Plotting the Grid of Sensory Overload: ‘The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time’ Opens on Broadway,” New York Times, October 5, 2014, accessed December 14, 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/20 141 10106/theater/the-curious incident-of-the-dog-in-the-nighttime-opens-on-broadway.html.

[x] Curious Broadway, “Creating Christopher’s World,” YouTube video, 2:08, May 29, 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6gMH285LvbM.