Theatrical design is a design of fact and fiction, a kind of design suspended between reality and fantasy. Designers construct an identifiable world, but one inevitably filtered by the artifice of performance and a creative, often collaborative, subjectivity. Still, theatrical design can be a signifying and significant lens into society’s preoccupations and perceptions. “As always,” observed Elaine Evans Dee, former curator of Drawings and Prints at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, “popular taste was reflected in the theater.”[i] The constructed world of the theater, through performance, narrative, and design, represents a society grappling with its understanding of itself and its place in time—whether via a design for a living room or a decadent palace, a sailor suit or an extravagant bustle, all on stage.

Cooper Hewitt, in its dedication to design as a process, houses a collection of nearly 137,000 works on paper, many of which demonstrate how the process of design can evolve into a material reality—or how the material reality of theater begins with design. In the ephemeral art of theater and performance, these documents of process—whether preparatory or presentation sketches anticipating construction in other media—are especially vital to cultural history, as they are often the only documents of what once briefly existed. The actual sets, costumes, and props made from them will be deconstructed and sadly consigned to a landfill or simply lost to time once the theatrical run is over or a theater is torn down. It is the drawn designs that will remain for posterity to see what once was conceived—should production photography not yet have existed or the photographs not be saved. The design process becomes the artifact. As stated in the wall text of the 1983 Cooper Hewitt exhibition Designed for Theater: “The visual aspects are temporary, only drawings and prints such as these remain to hint at the production’s actual appearance.”[ii]

The impetus of my research into Cooper Hewitt’s holdings of theatrical designs was serendipitous: Caitlin Condell, assistant curator and acting head of Drawings, Prints & Graphic Design discovered, while conducting other research, the 1983 checklist for Design for Theater. The checklist contained approximately 200 works on paper that were either designs explicitly for performance or prints relating to theatrical architecture. I found scores more designs by searching through many gifts to the museum; the objective was to fortify existing object records through cataloguing and additional research—and raise the curtain on an entertaining romp through history for theater nerds everywhere.

Theatrical design is one ticket to a broader understanding of design history. At times theatrical designers are reacting to technical innovations in other media, reflecting new aesthetic taste, or, in some cases, even forging new perspectives on their own. But their designs betray a dichotomous eye: they reflect the culture in which they are produced as much as they communicate ideas about the culture being reproduced, whether the play’s narrative takes place in the past or the present. The theater’s frequent depictions of other times and cultures, as well as its rich tradition of revivalism (not unlike design as large), stages a dynamic visual, material, and technical dialogue.

It is this interplay of theatrical past and present, its process and preservation, that winds its way throughout the range of Cooper Hewitt’s collection. The theatrical designs commemorate royal celebrations and Victorian mourning costumes by and for Tony Award winners, baroque fantasies that defined theatrical spectacle for centuries, simulations of sunsets and storm clouds, even otherworldly costumes for vaudevillian follies. The majority of the Cooper Hewitt designs come from two major sources: purchases of drawings and prints from the Italian collector Giovanni Piancastelli (1845–1926), and a series of gifts in the early 1970s from working designers, acquisitions that sparked momentum for the 1983 exhibition Designed for Theater mentioned previously. The Piancastelli collection offered an array of works from the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries; the latter gifts offered a chronological catch-up, refreshing the collection with works by major twentieth-century designers.

What follows is a selection of designs, ranging in chronology, geography, and intended use within the theatrical universe. Some honor longstanding buildings while others were never actually produced; some are by members of families of long-standing theatrical royalty, while others are by artists just dabbling in theater; some were used for Off-Broadway productions but then replaced when the production moved to Broadway and were no longer of any use, because—in the end—that’s show business. Here are some visual facts so that you can enjoy the fiction.

Drawing, Design for Stage Curtain: The Unsinkable Molly Brown, 1960; Designed by Oliver Smith (American, 1918–1994); USA; pen and black ink, brush and gouache, graphite on illustration board; 26.2 × 45.3 cm (10 5/16 × 17 13/16 in.); Gift of Oliver Smith; 1969-171-11

Drawing, Costume Design: Sir, for The Roar of the Grease Paint, the Smell of the Crowd, 1965; Designed by Freddy Wittop (American, b. Netherlands, 1911–2001); USA; brush and watercolor, graphite on gray illustration board; 50.8 x 38 cm (20 in. x 14 15/16 in.); Gift of Freddy Wittop; 1971-1-5

Print, Machines de Théatres (Theatrical Machinery), pl. XV, vol. 10 from Encyclopédie, ou, arts et des métiers (Encyclopedia, or a Systematic Dictionary of the Sciences, Arts, and Crafts), 1772; Designed by Robert Bénard (French, active 1734–1772); France; engraving on paper; 39.1 × 47.2 cm (15 3/8 × 18 9/16 in.); Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Richard B. Freund; 1977-86-34

Print, Interior View of the Academy of Music as Seen from Dress Circle, 1864; Lithographer: A. Brown and Company ; USA; lithograph on paper; 45.6 × 36.5 cm (17 15/16 × 14 3/8 in.); Gift of Hamill and Barker; 1961-105-150

Drawing, Stage Design: Scene II, Chair and Bed, for King Lear, 1990; Designed by Robert Wilson (American, b. 1941); USA; black pastel chalk on white wove paper; 66 x 97 cm (26 x 38 3/16 in.); Museum purchase through gift of the Advisory Council and bequest of Mary Hearn Greims and from Sarah Cooper-Hewitt Fund; 1992-90-1

Drawing, Stage Design: All the World Wondered, December 30, 1929; Designed by Henry Dreyfuss (American, 1904–1972); graphite, red crayon, pen and black ink on paper; 50.5 × 75.7 cm (19 7/8 × 29 13/16 in.); Gift of University of California, Los Angeles; 1973-15-119

Print, Edmund Kean as Richard III, 1839; Written by William Shakespeare (British, ca. 1564–1616); England; hand-colored engraving, embossed foil, fabric on paper; 23.2 × 28 cm (9 1/8 in. × 11 in.); Gift of Hamill and Barker; 1961-105-19

Drawing, Costume Design: Dancer to Perform on a Chariot for a Ballet, 17th century; Italy; pen and brown ink, brush and brown wash, black chalk, graphite on paper; 26.8 × 19.1 cm (10 9/16 × 7 1/2 in.); 1942-3-13

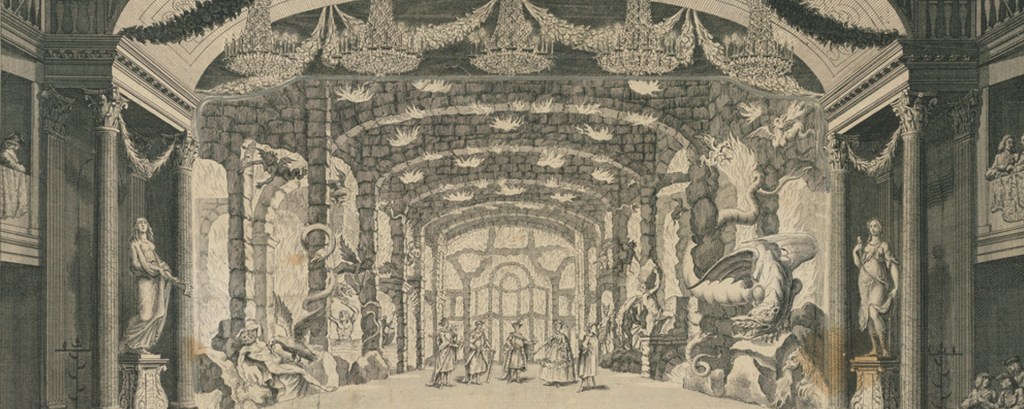

Print, Scene from a Tragedy, ca. 1650; Designed by Jean Le Pautre (French, 1618–1682); etching on paper; 21.5 × 31 cm (8 7/16 × 12 3/16 in.); Bequest of Erskine Hewitt; 1938-57-1450

Drawing, Stage Design: Prairie Church, for “Oklahoma” Film, ca. 1955; Music composed by Richard Rodgers (American, 1902–1979); USA; brush and watercolor, graphite on illustration board; 25.3 × 39.3 cm (9 15/16 × 15 1/2 in.); Gift of Oliver Smith; 1969-171-2

Drawing, Costume Design: Dancer in a Manège, for Ringling Brothers Circus, ca. 1941–57; Designed by Miles White (American, 1914–2000); USA; brush and watercolor, pen and ink on paper with attached fabric swatches; 37.7 × 27.7 cm (14 13/16 × 10 7/8 in.); 1971-4-11

Drawing, Stage Design: Rainstorm, for 110 in the Shade, 1963; Designed by Oliver Smith (American, 1918–1994); USA; brush and watercolor, graphite on illustration board; 11.4 × 20.3 cm (4 1/2 in. × 8 in.); Gift of Oliver Smith; 1969-171-15

Drawing, Costume Design: Christine, for Mourning Becomes Electra, 1969; Designed by Karl Eigsti ; USA; brush and watercolor, acrylic on paper with attached velvet swatch; 40.1 × 30.2 cm (15 13/16 × 11 7/8 in.); Gift of Karl Eigsti; 1970-52-3

Print, Section of the House and Proscenium, ca. 1720; Architect: Francesco Galli Bibiena (Italian, 1659 – 1739); engraving on paper; 24.8 × 34.1 cm (9 3/4 × 13 7/16 in.); Bequest of Erskine Hewitt; 1938-57-1439

Drawing, Costume Design: Chorus Men, for Susannah, 1965; Music composed by Carlisle Floyd (American, b. 1926); USA; brush and watercolor, graphite on paper with attached fabric swatches; 30.5 × 22.8 cm (12 × 9 in.); Gift of Jane Greenwood; 1970-56-4

Drawing, Stage Design: Variation of the Palace Terrace, Act I, Scene 2, for Don Giovanni, 1957; Music composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Austrian, 1756–91); USA; pen and black, red ink, brush and watercolor on paper mounted on cardboard; 15.6 × 12.7 cm (6 1/8 in. × 5 in.); Museum purchase through gift of Ogden Codman; 1958-138-1

Drawing, Stage Design: Variation of the Palace Terrace, Act I, Scene 2, for Don Giovanni, 1957; Music composed by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (Austrian, 1756–91); USA; pen and black, red ink, brush and watercolor on paper mounted on cardboard; 15.2 × 13.7 cm (6 × 5 3/8 in.); Museum purchase through gift of Ogden Codman; 1958-138-3

Drawing, Costume Design: Night Light, for Ziegfeld Follies of 1920, 1920; Designed by Charles LeMaire (American, 1897–1985); USA; brush and watercolor, graphite on heavy paper; 58.2 × 36.8 cm (22 15/16 × 14 1/2 in.); 1970-55-3

Drawing, Set Design: Curtain, for Ninette de Valois’s Checkmate, 1937; Music composed by Arthur Bliss (British, 1891–1975); USA; brush and gouache, graphite on heavy white paper; 35.4 x 54.6 cm (13 15/16 x 21 1/2 in.); Gift of Mrs. E. McKnight Kauffer; 1963-39-272

Drawing, Costume Design: Le Galant, for Le Testament, 1971; Music composed by Ezra Pound (American, 1885–1972); USA; brush and watercolor, gouache, pen and ink, charcoal, graphite on laid paper; 39.8 × 52 cm (15 11/16 × 20 1/2 in.); 1973-14-4

Print, Theater Interior with a Tight-Rope Walker, ca. 1800; Designed by Alexander Wilson (Scottish, active USA, 1766–1813); engraving on paper; 23.5 × 15.9 cm (9 1/4 × 6 1/4 in.); 1948-89-7

Drawing, Elevation of the Facade of the Theater, St. Petersburg, ca. 1860; Designed by Cesare Recanatini (Italian, 1823–1893); Italy; brush and gray, blue watercolor, pen and ink on paper; 18.8 × 25.6 cm (7 3/8 × 10 1/16 in.); Bequest of Erskine Hewitt; 1938-57-1421

Print, Theater Interior with Performance Taking Place, ca. 1740–60; engraving on white paper; 29.4 × 44.2 cm (11 9/16 × 17 3/8 in.); Bequest of Erskine Hewitt; 1938-57-1438

Drawing, Costume Design: Nora, Act I, for A Doll’s House, 1937; Designed by Donald Mitchell Oenslager (American, 1902–1975); USA; brush and watercolor, graphite on white paper with attached fabric swatches; 35.2 × 25.7 cm (13 7/8 × 10 1/8 in.); Gift of Donald Oenslager; 1960-226-11-a

Drawing, Stage Design, Prison in Gothic Building, mid- 18th–late 18th century; After Giuseppe Galli Bibiena (Italian, 1696–1756); Italy; pen and bistre ink, brush and wash on paper; H x W: 34.2 × 49.9 cm (13 7/16 × 19 5/8 in.); Museum purchase through gift of various donors and from Eleanor G. Hewitt Fund; 1938-88-452

Drawing, Design for a Theater Curtain, mid-19th century; Designed by V. Bertolotti (active 1850–1860); Italy; pen and black, blue ink, brush and watercolor, gouache, gold paint, graphite on wove paper; 23.5 × 39 cm (9 1/4 × 15 3/8 in.); Gift of Eleanor and Sarah Hewitt; 1931-73-276

Drawing, Costume Design: Hello, Dolly!, 1964; Designed by Freddy Wittop (American, b. Netherlands, 1911–2001); USA; brush and watercolor, graphite on gray paper; 43 x 46.2 cm (16 15/16 x 18 3/16 in.); Gift of Freddy Wittop; 1971-1-10

Drawing, Elevation of the Facade of a Theater, Prague, ca. 1860; Designed by Cesare Recanatini (Italian, 1823–1893); Italy; pen and ink, brush and sepia, blue, green wash on cream paper; 19.6 × 26.4 cm (7 11/16 × 10 3/8 in.); Bequest of Erskine Hewitt; 1938-57-1423

Drawing, Design for Theater Ceiling, ca. 1820; Designed by Giuseppe Borsato (Italian, 1770 – 1840); Italy; pen and black ink, brush and watercolor, gouache, graphite on paper; 33 × 27.7 cm (13 × 10 7/8 in.); 1940-21-23

Drawing, Ground Plan and Elevations of Theater Boxes, Probably for the Teatro del Versaro (later Morlacchi), Perugia, Italy, 1778; Designed by Giuseppe Barberi (Italian, 1746–1809); Italy; pen and brown ink, brush and brown wash, graphite on off-white laid paper; 46.6 x 38 cm (18 3/8 x 14 15/16 in.); Museum purchase through gift of various donors and from Eleanor G. Hewitt Fund; 1938-88-116

This essay first appeared as “Raising the Curtain: Theatrical Designs in the Collection of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum” in Objective, The Journal of Design History and Curatorial Studies, Parsons School of Design, Spring/Summer 2017.

[i] Elaine Evans Dee, Designed for Theater: Drawings and Prints from the Cooper-Hewitt Museum, The Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of Design (Detroit: The Detroit Institute of Arts, 1984), 3.

[ii] Wall text, Designed for Theater, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York.